Dear one,

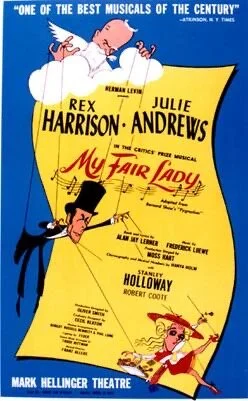

The other evening we heard Nostalgia cooing: “It’s been decades: why not take delight once again in viewing My Fair Lady? Audrey Hepburn and Rex Harrison played their roles so well.”

So, heeding that call, initially we were delighted: the sets, the costumes, and the wedding of lyrics and music—and yes, the acting. And so it was for several days the lines: “I could have danced all night …”, or: “Get me to the church on time …”, or: “Words, words, words I’m sick and tired …” echoed throughout the halls of my mind.

However, I then recalled that My Fair Lady is the musical adaptation of George Bernard Shaw’s play, Pygmalion, which has a very different ending than that of My Fair Lady. In Shaw’s original play, and its sequel, Henry Higgins—the irascible, aristocratic scholar and phonetician—and Eliza Doolittle—the flower girl, whom he transforms into a “fair lady”—do not reconcile; rather, Henry remains the insensitive, self-absorbed bachelor and Eliza marries Freddy Eynsford-Hill, a would-be aristocrat, and together their family life centers upon a barely respectable flower shop.

Presumably, from Shaw’s perspective the 1913 divide between London’s aristocratic classes and its Cockney classes was unbridgeable. In reality, Henry could not marry Eliza, or even if he did, theirs would be a “legal fiction,” a marriage in name only. Moreover, Shaw also sought to highlight the emptiness of aristocratic life, hidden behind a veil of glamor and glitz. With thought, even though My Fair Lady encourages us to suspend our disbelief, it too conveys the same message: money and manners, erudition and eloquence give the appearance of life, but only the appearance.

As I thought further regarding “appearances,” I recalled the “letter” written to the church in Sardis (Revelation 3:1-6): “You have the reputation of being alive, but you are dead.” For nearly 800 years, Sardis appeared vibrant and alive: a city of wealth, power, and fame—even of the legendary King Croesus and his gold—bt by the end of the first century our era, it was a city only of appearances. Today its ruins are the site of a poor, Turkish village.

Shaw’s message about appearances, although contemporary, is nothing new: appearances are not necessarily the reality. However, Shaw provided little hope, whereas the concluding words to the church in Sardis are these: "[Some] will walk with me in white … and I will never blot [their names] from the book of life” (3:4-5).

Not an appearance: The One who walks in white gives Life abundantly.

Stan